Transactional Updates in Leap 15 & Tumbleweed

4. Apr 2018 | Richard Brown | No License

Transactional Updates is one of the exciting new features from the Kubic project which will be available in the upcoming release of openSUSE Leap 15, and is already available in Tumbleweed.

But what are they, and why should you be interested?

Patching isn’t Easy

Software updates have two common, but often conflicting requirements. Everyone should update as soon and as often as possible to ensure they are running the latest, most secured versions of their software. Without this, there is a greater risk of software failure or successful cyber attacks against your system.

But at the same time, no one wants to risk their currently running system. “Never touch a running system” is a mantra which many sysadmins and users around the world stick to, with good reason. Software updates do come with an element of risk, and this risk has a habit of increasing on systems with more users and more packages. Sooner or later, something can go wrong.

This is a problem we’ve long wrestled with in openSUSE & SUSE distributions. In Tumbleweed we release updates at a breakneck pace, hundreds of new packages a week. Users want and need these updates as close to that pace as they can handle, but want a minimal risk.

In the world of SUSE’s Enterprise distributions, the demands are no easier. Mission Critical systems often have extensive solutions for high availability, so updates that disrupt the uptime of a service are more expensive than regularly rebooting a system. In these environments it’s also very important that updates are applied perfectly. Changes should be applied completely with the system never left is an undefined or questionable state.

Snapshots - The Beginning of the Answer

In all current openSUSE & SUSE Linux Enterprise distributions we use btrfs with snapper by default to offer our users baked in snapshots with rollback.

These are integrated with zypper and YaST to automatically record the system state before and after any software or configuration changes by these tools.

This goes some way to address some of the problems. Snapshots do provide a very reliable way of restoring the system to a working state, but ultimately this approach does not mitigate many of the problems that can break the system in the first place.

These “traditional” updates are run against the running system, and thusly they can impact and be impacted by services currently running. These dynamic variables can more likely lead to a situation where an update fails or only partially succeed, meaning that need for rolling back a system can actually happen more often than it should.

Introducing Transactional Updates

Put simply, a Transactional Update is an update that is:

Atomic. It is either fully applied, or not at all. Also the update is accomplished as a single transaction, that does not influence the running system.

Easily reverted. If an update fails, or if the successful update is deemed to be incompatible or otherwise incorrect, it can be quickly discarded to immediately return the system to its previously functioning state.

What about…?

As customary when introducing anything new to the open source world, it is only fair to acknowledge there are already alternatives to this new Transactional Update approach.

For a long time, some users have used the rather expensive approach of maintaining multiple versions of their system in multiple partitions on disk, to be able to easily switch between them and address many of these problems. Of course it works, but it’s rather expensive in terms of disk storage and maintenance effort.

Looking for a more modern approach, there are solutions like ostree & snap which attempt to address these problems and bring atomic/transactional updates to their users.

These solutions are not without their benefits, but come with some key flaws which Transactional Updates avoid. Namely they require users, developers, and partnering software vendors to all learn new ways of managing their systems. Existing packages cannot be re-used, requiring either repackaging or conversion. And existing repositories and other common package delivery mechanisms are no longer available.

All of this develops to a situation where adopters need to redesign their mindsets, systems, tools and company policies to work with these tools. And that is something Transactional Updates strives to avoid.

Keeping it simple

Under the hood, we have worked hard to keep Transactional Updates simple. We are utilising the same btrfs, snapper, and zypper technologies we know and trust by default in openSUSE and SLE.

At its heart, Transactional Updates does something very similar to our traditional snapshots with rollback. But with Transactional Updates it never touches the running system.

Instead of patching the current system, the transactional-update tool creates a new, empty, snapshot. All of the operations required by the update are carried out into that snapshot, ensuring the current system is untouched with no changes impacting the running system.

At the end of the update, assuming the update is successful, this completed snapshot is marked as the new default. These updates then take effect when the system is rebooted.

If the update was unsuccessful, the snapshot is discarded and no change is made to the system.

One additional benefit of this approach, because all of the update processing is done in the running system, the boot time of the transactionally updated system is identical to the regular boot time of a non-transactional openSUSE system.

The Icing on the Cake: Read-Only Root File System

Transactional Updates never touch the running system, but you might, or so might other running software. On a system with a typical read-write root filesystem, this means that there are still variables which can interrupt, interfere, or otherwise interact with a system update.

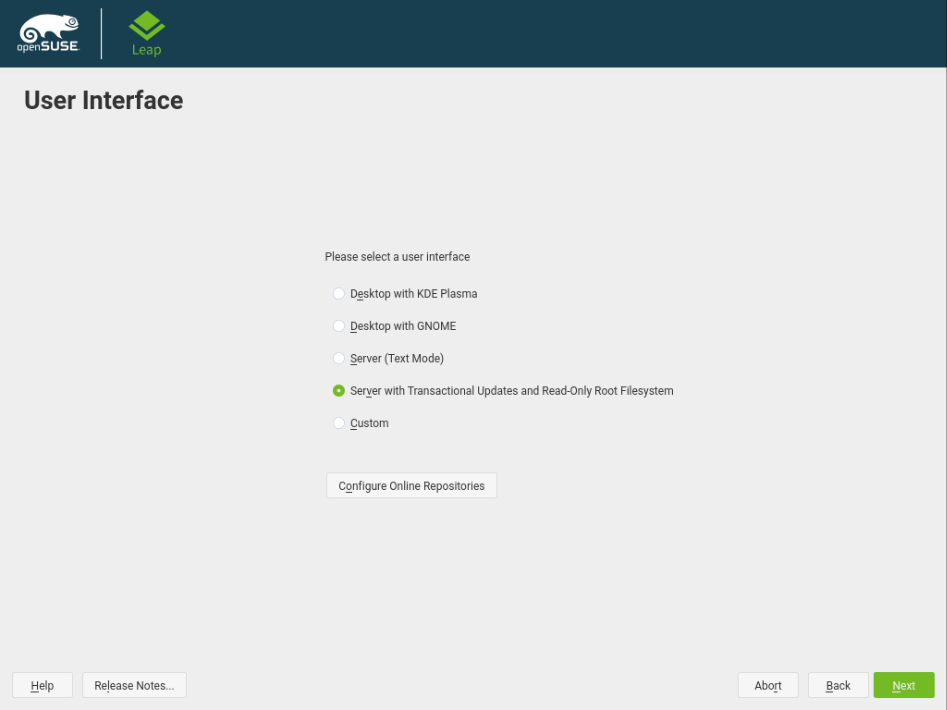

And yet in many cases, users do not need to be able to write to their root filesystem. This is why in Leap 15 and Tumbleweed we’re excited to now offer the Server with Transactional Updates & Read-Only Root Filesystem System Role.

Introducing the Transactional Server role

User configuration in /etc is writable by virtue of an automatically configured overlayfs and /var is writable for services as it is now a separate subvolume.

This role shares many similarities with SUSE CaaS Platform and Tumbleweed Kubic where this feature is used by default to provide a Container Host or Kubernetes Cluster Node.

But now the feature is also available in openSUSE Leap 15 and Tumbleweed there are even more possibilities. Do you want to be even more sure than usual that your web or mail server is patched regularly without breaking? How about your Virtualisation Host? What about IoT? Maybe even a transactional desktop?.

Using Transactional Updates

The easiest way to use transactional updates is to select the appropriate role during a Leap 15 or Tumbleweed installation.

System Role selection screen in openSUSE Leap 15

Once installed, just use transactional-update as the replacement for zypper or yast for upgrading, updating, or removing the software on your system.

The syntax should be rather familiar:

- Update your system with

transactional-update upon Leap, ortransactional-update dupon Tumbleweed - Install software with

transactional-update pkg in $foowhere$foois the name of the package you want to install - Remove software with

transactional-update pkg rm $foo

After any of the above, you need to reboot your system before the changes will take effect.

- To throw away a pending snapshot, just run

transactional-update rollbackbefore rebooting - In the unlikely event of a

rebootnot booting successfully, just choose the last working snapshot from the systems grub menu, then runtransactional-update rollback

Enabling Automatic Transactional Updates and Reboot

Transactional Updates can be set to automatically run daily by simply running systemctl enable --now transactional-update.timer

This is rather useless however without some automated way of rebooting the system. Rather than a dumb cron job, we recommend using rebootmgr. It can be enabled by running systemctl enable --now rebootmgr.service.

By default rebootmgr will reboot a system sometime between 0330 and 0500 if an update is pending. Edit /etc/rebootmgr.conf to configure the rebootmgr service to change this maintenance window to suit your needs. man rebootmgr.conf provides details on the parameters available.

That’s it, you now have fully automated transactional system for whatever you want to run.

Thanks, happy transactional updating, and have a lot of fun!

Categories: blog

Tags:

Kubic - Retired

Kubic - Retired